Tenontosaurus

Name Origin

Tendon Lizard

Classification

Diapsida, Ornithischia, Ornithopoda

Habitat (Discovery Location)

United States

Period

Approximately 122–110 million years ago (Early Cretaceous)

Length

Approximately 6.5 meters

Weight

Approximately 1–2 tons

Diet

Herbivore

![[Latest Research] What Was the Function of Spinosaurus's Giant "Sail"? Exploring the Mysteries of Thermoregulation and Underwater Locomotion](https://dinosaurmuseum.jp/wp/wp-content/uploads/eyecatch_spinosaurus-sail-function_en-1024x512.webp)

![[Latest Discovery] A Third Type of Skin, Neither Scales Nor Feathers? Meet "Haolong dongi," a New Dinosaur Species Covered Entirely in Spikes](https://dinosaurmuseum.jp/wp/wp-content/uploads/eyecatch_dinosaur-spiky-skin-discovery_en-1024x512.webp)

Description

The North American continent during the Early Cretaceous period (approximately 110 million years ago).

In this era, before the appearance of Tyrannosaurus, there was a herbivorous dinosaur that flourished and supported the base of the ecosystem.

Its name was “Tenontosaurus.”

At first glance, it appears to be an unassuming medium-sized dinosaur, but they are extremely important in paleontology.

This is because numerous pieces of evidence have been discovered showing the dramatic “kill-or-be-killed” relationship they had with the famous carnivorous dinosaur Deinonychus.

Origin of the Name “Tendon Lizard” and the Massive Tail

Bundles of Strong Tendons

The scientific name Tenontosaurus means “tendon lizard” in Greek.

This name derives from the bundles of “tendons” connecting bones and muscles along the spine, particularly from the hips to the tail, which developed into a mesh-like structure and were so ossified that they remained as fossils.

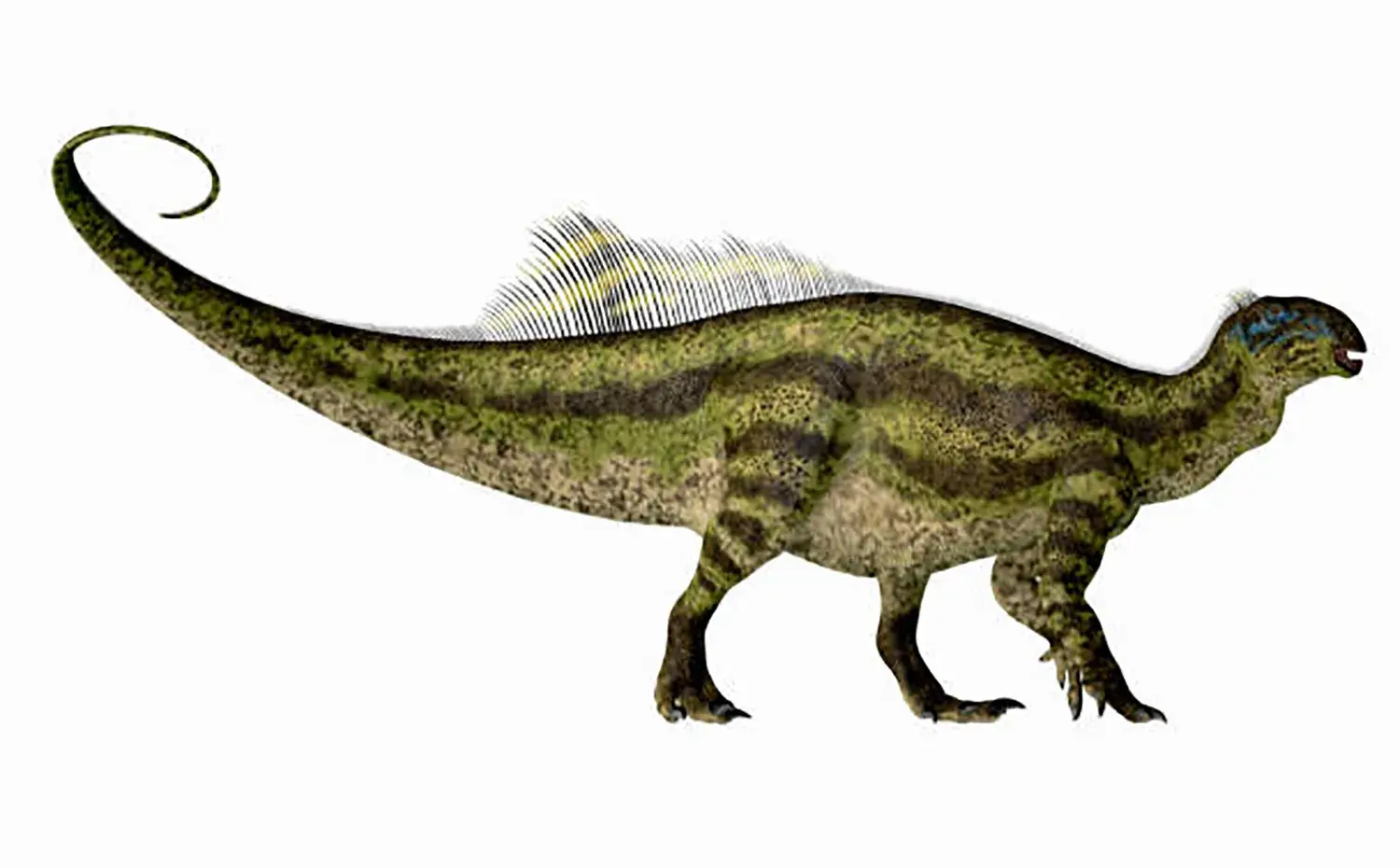

A Tail Taking Up 60% of Total Length

Although its total length was about 6.5 meters, the “massive tail” accounted for more than 60% of that length.

The tail accounted for 60% of the total length

This tail was not only long but also broad vertically and firmly reinforced by tendons.

It is believed that this tough tail played a significant role beyond merely serving as a balancer (described later).

A Quadruped Similar to but Different from Iguanodon

Unique Proportions

It was once thought to resemble Iguanodon, but the following differences exist:

Forelimbs

It lacked the spike-like thumb seen in Iguanodon; it had five fingers, and the forelimbs themselves were long.

Neck

Shorter compared to Iguanodon.

Lifestyle

They basically lived as “quadrupeds,” walking with their long forelimbs on the ground.

Their diet consisted of grass and leaves from low trees near the ground, which they plucked with the beak at the tip of their mouth and ground down with their back teeth.

It plucked food with its beak and ground it with its back teeth.

A Wandering Taxonomy

Initially classified as a small Hypsilophodont, it was later found to be closer to Iguanodonts.

Currently, it is often classified in its own “Tenontosauridae” family or as a “Rhabdodontomorph,” making it an important specimen for understanding the evolution of ornithopods.

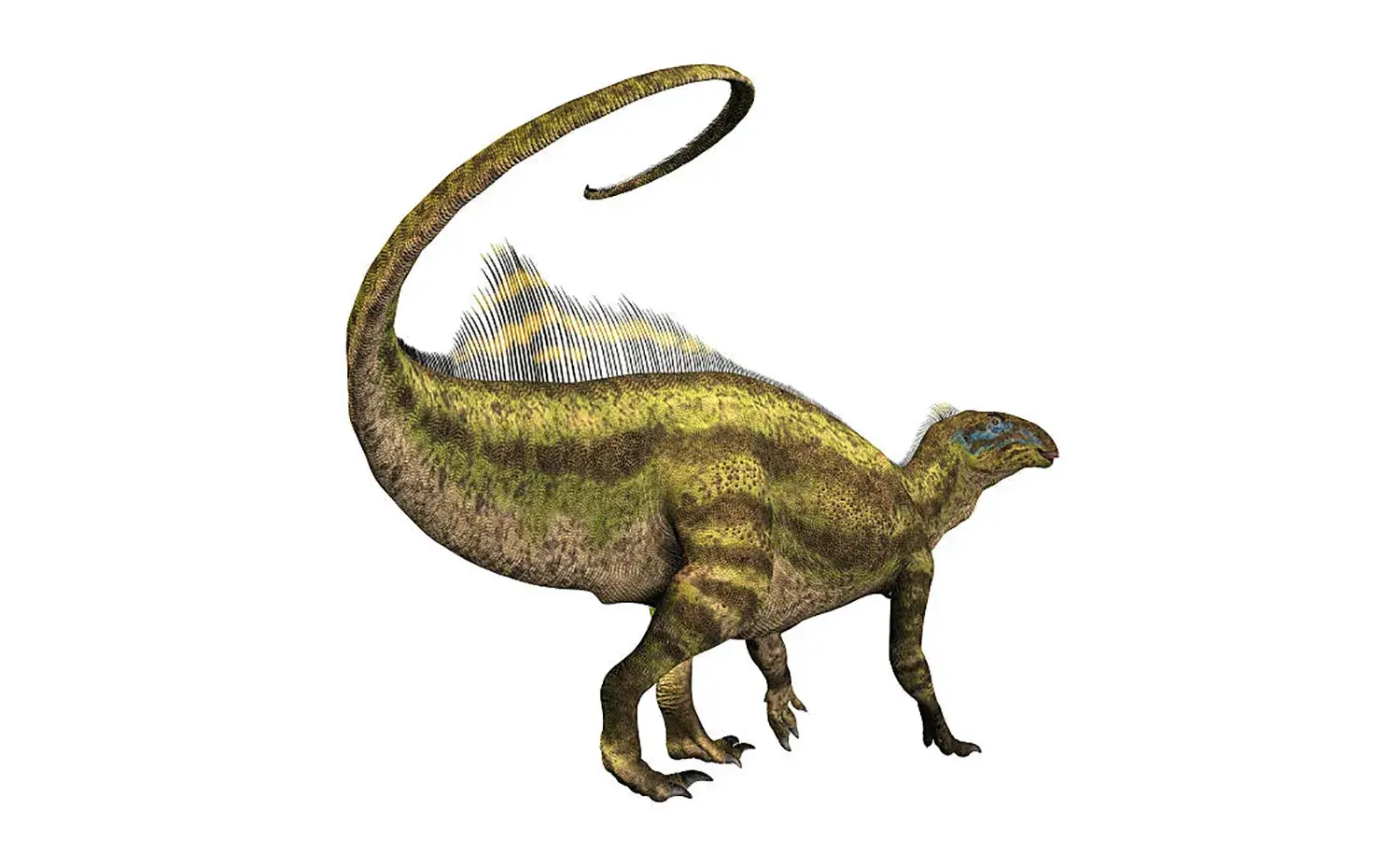

The “Deadly Battle” with Deinonychus and the Tail Weapon

As the “most numerous herbivorous dinosaur” in North America during the Early Cretaceous, Tenontosaurus was the perfect prey for carnivorous dinosaurs.

Relationship with Deinonychus

Particularly famous is its relationship with the small carnivorous dinosaur “Deinonychus.”

Cases have been reported where the bones of multiple Deinonychus were found near a single Tenontosaurus fossil.

This is evidence that they were routinely attacked, and for a long time, it served as the basis for the theory that Deinonychus “hunted in packs (pack hunting).”

*While a “scavenging (swarming dead bodies)” theory exists today, there is no mistake that they had a predator-prey relationship.

Routinely attacked by Deinonychus

The Deadly “Tail Strike”

When attacked, Tenontosaurus did not merely run away.

By swinging its tough tail—which made up 60% of its total length—using its powerful muscles, it became a terrifying “whip-like” weapon.

The tough tail became a “whip-like” weapon

The Deinonychus carcasses found alongside the fossils might have been unlucky hunters who were killed by a counterattack from this tail.

Survival Strategy: Rapid Growth

One of the reasons they were able to flourish so well lies in the “speed of their growth.”

It has been revealed that they reached sexual maturity at only about 8 years old; even though many were eaten by predators, they survived as a species by becoming adults and leaving offspring even faster than they could be consumed.

“Even if eaten in large numbers, they multiply even more.”

That was the secret to their strength and the underlying power that supported the Cretaceous ecosystem.